Introduction to Humane Education

Humane Education (HE) has been defined as:

"A process that encourages an understanding of the need for compassion and respect for people, animals and the environment and recognises the interdependence of all living things."

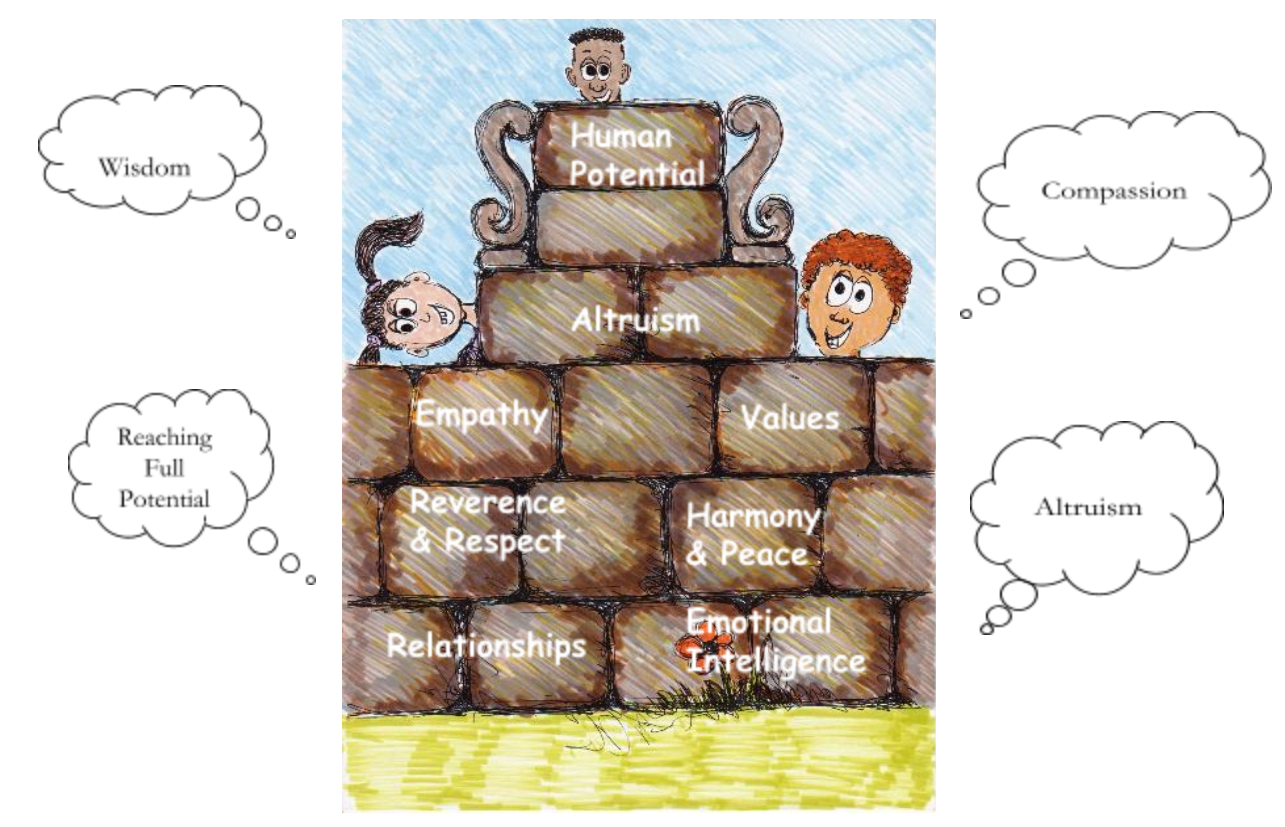

HE is about creating a more just, humane and sustainable world for people, animals, and the earth through education. It is also a “root” intervention to develop populations socially, psychologically and ethically.

There are a large number of HE programmes around the world, and even an Institute for Humane Education in the USA. Practitioners across the world report that it has a multitude of positive outcomes, including the development of self-worth, well-being and human potential. The Institute for Humane Education describes its ultimate outcome as the creation of a generation of “solutionaries” – altruistic people who are committed to doing the most good and least harm.

Introduction to the Malawi Humane Education Pilot Project

Background

The Malawi pilot project was specially developed using lessons and pedagogy designed to inspire positive attitudes, values, and action through the exploration of a wide range of issues including social justice, human relationships, the environment, and animal welfare. In developing the programme, we also identified and included key values and qualities which are important to happiness and well-being, including: Compassion, kindness; altruism and service; values; wisdom; and harmony with nature. Then we added a special unit on fulfilling human potential (flourishing). The result is a foundation course of 20 lessons in a comprehensive Teachers Guide, pulling together international “best practice”.

This course was piloted in Malawi over the period of one school year (2016-2017). It was conducted in four schools after formal school hours, with the support of education stakeholders. Two urban and two rural schools were included: Chimutu and Shire in Lilongwe, and Chidewele and Thete in Dedza.

The pilot was subjected to full professional Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E). Monitoring included reporting of the outcomes of each lesson and monthly feedback interviews. Evaluation included baseline and final reports from both teachers and learners and assessed a broad range of outcomes including: educational and class behaviour; well-being; social skills; and qualities such as harmony with nature, compassion, kindness and altruism/service.

The Briefing Note for countries on the 2015 Human Development Report recorded that Malawi was ranked at 173 out of 188 countries and territories in the 2014 Human Development Index. UNDP indicates that about 85 percent of its population is living in rural areas. This is why it was vital to include rural schools in the pilot project.

Teachers Guide

The Teachers Guide includes twenty full lesson plans, including worksheets (which can be copied for classroom use) and further information on “issues to explore”. The lessons include:

Animals and Us:

- Our Animals, Our Happiness

- Animals Have Feelings Too

- Kindness: It’s in the Bag

- Animal Parliament

- Animal Happiness Volunteers

Nature and Us:

- Minding Nature

- Web of Life

- Nature is Speaking

- Eco-Volunteers

Other Humans & Us:

- Perception

- Double Vision

- Caring Class

- Communication

- Tolerance

- Bullying

- Human Happiness Volunteers

Fulfilling Potential:

- Reaching Potential: Who Am I?

- Reaching Potential: What Shall I Be?

- Superheroes

- Greatness

A Collaborative Project

This was a collaborative project, with a number of stakeholders. These included:

- World Animal Net (WAN): WAN’s Co-Founder, Janice Cox MBA, was responsible for course development and project management.

- The Lilongwe SPCA (LSPCA) was responsible for local organizations and lesson delivery by two LSPCA humane educators (Edson Chiweta and Esimy Chioza, managed by CEO Lieza Swennen).

- The RSPCA International supported and funded the project.

- The Intercultural Center for Research in Education (INCRE) was responsible for project monitoring and evaluation.

- The Centre for Education Training and Research at the University of Malawi (CERT) provided professional support and advice, and local evaluation.

- Link Community Development (LINK) also provided technical advice and local monitoring.

The district education authorities covering Lilongwe Urban and Dedza Rural were both supportive of the project and offered advice and encouragement.

Project Experiences

There is a full professional evaluation of the project in a separate Final Evaluation Report, compiled by Dr. John Zuman of the Intercultural Center for Research in Education.

This report is an informal account of our project experiences and has been compiled from individual lesson reports, monthly feedback interviews and project assessment visits (which included visits to all four schools to observe lessons).

The feedback from educators, learners, teachers, and patrons/matrons and stakeholders has been overwhelmingly positive. There is more detail on this below.

Lesson Planning

Because of the short lesson time available, the majority of the lessons had to be broken down into two halves. This led to additional planning. However, the team worked through the Teachers Manual and broke down each lesson into appropriate sessions. It was also decided to give more time at the end of each section (animals, nature, and people) for an active community study and project using the lessons learned. This helped community involvement, acceptance, and outreach. Using this approach, the 20 lessons in the Teachers Manual fitted neatly into one academic year.

Edson and Esimy, the Humane Educators, planned lessons together well in advance, to ensure that they were delivered in the same way. In case of any potential problems, they consulted the Project Manager to discuss approach.

Lesson Observations

Lessons were observed by the Project Manager and a variety of stakeholders including Professor Banda from CERT, Michael Mulenga from Link Community Development Dedza and Mr. Kachikuli, Coordinating Primary Education Advisor (CPEA). All observers agreed that the lessons went extremely well. The educators were excellent, and the learners absorbed and attentive. Active learning and participatory methodology helped to involve and interest the pupils. The educators had pre-planned the lessons and adapted these to the local situation and reality. They were also adaptable/flexible in class and able to address any points or situations which arose spontaneously during the course of the lessons.

At the beginning of the programme, there were concerns about Chidewere school, as the learners were very quiet and unforthcoming. However, by the time of the first assessment visit they had become used to the educator and new participatory methodology, and were engaged and paying full attention. It is possible that they had previously only experienced rote learning, and were kept silent in classes.

Humane Educator Feedback

The Humane Educators provided standard reports for each lesson delivered. These include aspects such as attendance, learner engagement, lesson success and details of any adaptations made. School conditions were difficult, but the educators adapted lessons accordingly. These adaptations have now been included in revisions to the Teachers Guide, and demonstrate that the course is possible everywhere.

The Humane Educators reported that Head Teachers and school staff were very engaged. Sometimes the Head Teacher or Deputy attended and observed the lessons themselves. Teachers and support staff (Matrons/Patrons) were very interested and involved.

Monthly Feedback Interviews

The Project Manager carried out monthly feedback interviews, using structured questions designed by INCRE. The findings from these were interesting and positive.

A marked difference was found between the attitudes of urban and rural learners. This is attributed to lower educational standards and less awareness of the issues in rural schools. Thus, more explanation was needed for rural schools. For example, rural learners did not understand about captive animals (even when some instances were explained i.e. zoos, sanctuaries etc.). They had simply not been exposed to captive animal situations. On the other hand, they mostly stressed uses of animals (for example, farm animals providing food; working animals; pets for security and catching mice; wild animals for tourism, jobs, economic benefits). Urban children included pets as companions/friends - nice to have around – and birds as being beautiful to look at.

Retention rates for learners taking part in the pilot project were much better than usual school retention rates, with Malawi schools having high rates of drop-out. There were higher drop-out rates in rural areas, and it was explained that some learners live far away from school, and in the rainy season, the roads become bad (and in some cases impassable). Indeed, some learners were not able to attend school at all during the rains.

In Shire school, some learners dropped out and others were substituted. The new substitutes were also given baseline questionnaires, albeit a little later than the initial intake. In Chimutu school, a few learners were transferred (and were identified as such). In each case, the Humane Educators try to discover reasons for drop-outs as these happened (including seeking advice from teachers/matrons/patrons). However, drop-out rates were not high enough to be a major concern (and well below normal class drop-out rates).

The most successful lesson was the “Animal Parliament”. This involved learners making animal masks, and the acting out animal roles (and presenting species-specific animal concerns) in a staged Parliament session. The learners loved active, participatory approaches, and in the Parliament session, many “animals” made thoughtful interventions. By way of example, the elephant stated that the way humans treated it is unacceptable and is leading to extinction.

Another popular lesson was “Animal Happiness Volunteers”, because this involved studying problems, thinking more deeply about these, and planning actions to deal with them. This action-orientation was greatly appreciated. This lesson took place over three weeks, with the first two weeks spent looking into problems in the community, and the third week working on the development of a club with actions to deal with these. Here again, the rural schools found project selection more difficult, due to unfamiliarity with animal issues. But the project chosen by the Urban schools was excellent - awareness of the need for spay-neuter and dog population control. This was carried out in the community, led by the learners (supported by LSPCA).

Overcoming Teething Problems

There were some minor teething problems with the pilot, but these had been quickly addressed. In some cases, this involved minor adaptations to suit local situations and conditions (e.g. lack of a permanent, secure classroom and certain teaching aids). The Humane Educators did this very resourcefully and thoughtfully, overcoming any potential problems. Another difficulty was with the provision of food (which was introduced to assist concentration and retention). Originally, the LSPCA brought food to the learners, but some parents were afraid that this could be poisoned! So the system was changed so the LSPCA provided funds for the food, and the school provided this, with parental involvement. Finally, the reticence of the learners at Chidewele School was overcome when the humane educator won over their trust and confidence, and slowly introduced them to participatory methods in a non-threatening environment.

As noted above, the rural schools took longer to adapt to participatory methods, and the learners appeared less well developed educationally, and less familiar with the issues covered by the course. However, this situation improved steadily over the course of the year.

Positive Stakeholder Feedback

Prof. Banda of the Malawian Centre for Education Training and Research was extremely positive and supportive of the pilot. Interestingly, he said that the new Malawian school curriculum was meant to touch "head, hands, and hearts", but in practice, it had reached heads, very little hands (only a small amount of practical work), and was not touching hearts. But the Humane Education project helped to fill that gap.

Michael Mulenga from Link Community Development commented that the programme helped enormously towards learner retention because it was interesting and “the children loved it”! This is of vital importance, given the high drop-out rates of Malawian learners. The National Education Profile’s 2014 update showed a survival rate of learners to Grade 5 of just 55% female and 56% male.

The representatives from Lilongwe Urban district were also supportive of the project. The Desk Officer for Primary Education (sitting in for the DEM) pointed out that the HE project will help the learners in other subjects as well.

Lilongwe Urban appreciated the time and interest taken by the LSPCA. They rarely have NGOs helping their district with education (as most support goes to rural areas).

Monitoring and Evaluation

Monitoring and evaluation tools will be shared freely, so others interested parties can also benefit from these. In particular, animal protection societies may wish to replicate the project, in order to support local advocacy for inclusion in their school curriculum. These have been amended and simplified to take account of teething problems in this first pilot.

The Possibility of Curriculum Inclusion in Malawi

Humane Education has the potential to be transformational education, which moves the heart to make positive change. Given the success of the project, we discussed what would be needed to roll this out. Claxton Chipakha of Link Community Development advised that the appropriate curriculum areas would be life skills and social and environmental sciences.

The District Education Authorities at Lilongwe Urban advised that emerging issues could be included in their monthly report to the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (MoEST). There was also the possibility of the District Education Manager (DEM) requesting a meeting with the Director of Basic Education.

There is also a civil society education coalition in Malawi, which the LSPCA could join to support advocacy for roll-out.

Further Roll Out/Maximising Impact

The educational resources and results of this pilot project will be shared internationally. They will also be used to support advocacy in favor of HE in curriculums across the world, and also to enrich and influence development models which measure societal success beyond economic output. These include emerging new development paradigms which are under consideration by the United Nations, including Happiness/Well-Being (which is already introduced and measured in a number of policy arenas, including the OECD) and Harmony with Nature.

All the teaching and M&E resources and tools will be shared with interested animal protectionists and educationalists.

Janice H. Cox, MBA

Director – World Animal Net/Humane Education Project Manager

November 2017