The Animal Welfare Movement

Introduction

Movement Building for Social Success

Barriers to Success

Threats

Previous Successes

What is Needed for Success?

Introduction

World Animal Net (WAN) resources include further background information on the animal welfare movement, including: ‘What is Animal Welfare?’; ‘Ethical and Philosophical Theories’; ‘History of the Movement’; and ‘Religion’

The animal welfare movement is clearly a social change movement, as it seeks to change society’s perception and treatment of animals. However, as noted by World Animal Net in ‘The Animal Protection Movement and its Progress’, it is taking a long time to ‘come of age’ as one of the world’s great movements for social change. This section will examine some of the reasons for its protracted march towards ‘take off’ as a movement.

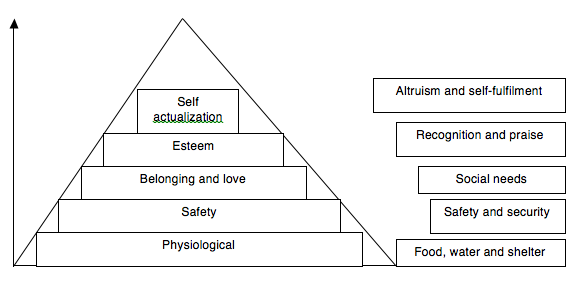

The animal welfare movement often views itself as somehow separate from other social change movements. However, as this course has shown, there is much to learn from other social change movements. Also, as with any similar movement, the animal welfare movement cannot be isolated from social change, politics, culture and economics. In fact, the development of the animal welfare movement is strongly connected to these areas. Also, as this is a highly altruistic concern, it is often considered necessary to tap animal welfare into other social causes that involve human needs which are ceded higher ranking/urgency by policy-makers. However, this approach should be viewed as an expedient, rather than a solution, as it will only lead to change in areas where animal welfare aligns with other (predominant) interests. Until fundamental and underlying moral values are changed to recognize the importance of animal welfare in its own right (for reasons such as animal sentience, justice, international acceptance etc.), then animal welfare will continue to lose out whenever it clashed with other human-centered interests.

The animal welfare movement is in different stages of development in different countries. Culture and historical development impact upon the status of animal welfare and the stage of the movement’s development. Culture and society also impact upon the way in which the animal welfare movement can carry out its advocacy for best impact. Religion can also impact upon attitudes towards animal welfare, hampering or advancing the cause.

There is a vast difference in the way the animal welfare movement is perceived by different organizations and individuals. Some view it as simply a compassionate welfare activity, whereas others view it as a real movement for social change: they see the underlying injustice in the way that current systems treat our fellow animals and burn with the desire the see the situation righted, not just ‘sticking plaster’ solutions applied to the existing flawed, unjust and cruel system.

In reality, the animal welfare movement is quite clearly one of the great movements for social change, although it is taking a relatively long time to ‘come of age’, and is in different stages of development in different countries. It is interesting to note that many individuals who championed causes of human welfare also campaigned against cruelty to animals (for example, William Wilberforce and others who campaigned to abolish slavery; great Victorian reformers such as Lord Shaftesbury, Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill; black spokesmen such as Toussaint L'Overture of Haiti; and even Abraham Lincoln). The principle of social justice requires a developed sense of empathy; as does compassion for the plight of animals.

Our ethical foundations (especially in the West) have evolved as a human-biased morality, but the past 30+ years have brought a significant change. Both the animal rights and the Green movements have shifted the focus of attention to include the non-human world.

This perspective is, in fact, not at all new. The ancient, yet living traditions of Native Indians and Aborigines show a reverence and understanding for the natural world, which combines a respect for the sustainability of the environment with a care for the individual animal.

Thankfully, as with many fields of moral concern, the ethics of animal welfare have been following an evolutionary trend, and the current climate is one in which the status and well-being of animals is attracting well-deserved attention even though “exploitation of them has become been ingrained into our institutions”(Midgely). The current climate, though, is one in which leading philosophers and religious figures actively debate and write about various viewpoints on animal welfare; the media frequently highlights welfare issues; governments throughout Europe and beyond feel growing pressure from their concerned electorates in respect of animal welfare issues; consequently, parliaments (including the European Parliament) debate and legislate on animal welfare and respected fora such as the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) and the Council of Europe (the bastion of human rights in Europe) prepare standards, conventions and recommendations covering the welfare of animals in different situations. Even organizations such as the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations and the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation (IFC), with vastly different priorities are now including animal welfare in the sphere of their activities.

Animal welfare has now become an international issue. Over the last 30 + years it has evolved from a marginal local or, at best, national issue into one that is on the international political agenda. At the same time, the industry has become international – both in terms of its business activities and its political pressure. There is also increasing ‘internationalization’ of culture, which presents the movement with both an opportunity and a threat. The world is facing a relentless increase in consumerism and ‘Americanization’, and with this the massive expansion of animal use industries (including producers, fast food giants and supermarkets). The onus is now on the movement to ensure that the animal welfare culture is spread internationally to counter these threats.

Movement Building for Social Change

The study of social change shows the clear importance of movement building. The major frameworks for social change all include the need for movement' organization, leadership development and education.

Analysis in this course and other sources provides a sound indication of the key success factors in movement building for the achievement of enduring social change.

If we consider what is needed to bring about social change, we need education and awareness of our issue and strategic advocacy to bring animal welfare higher up in society’s social and political concerns. To equip the movement for this task, we need strategic movement development that can learn from other inspiring social change movements (see above).

One important lesson from other inspiring social change movements is that this movement building is not purely strategic and organizational... A key factor is the firing-up and spreading of what Gandhi termed ‘Satyagraha’ – truth, firmness or more vividly: ‘soul force’. We must never underplay the moral strength of the animal welfare cause, or the need for justice for animals. We are the spokespeople for the animals, and if we don’t speak out as powerful advocates for their cause then nobody will.

Barriers to Success

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) was the world’s first animal welfare charity. It was founded back in 1824. The first international animal welfare organization was the World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA). WSPA was founded in 1981, but its origins were back in 1953. It was established from the merger of two international animal welfare organizations (the World Federation for the Protection of Animals founded in 1953 and the International Society for the Protection of Animals (ISPA), founded in 1959).

Despite being established so long ago, and having many well-resourced and influential organizations, many still feel that the international animal welfare movement has not reached its full strength and potential. This could be attributed to many reasons, including the following:

- Until recently, there have been no international legislation or policy initiatives around which the movement could unite.

- Lack of urgency about the mission

- Lack of ‘fire in the belly’ from many of the movement’s leaders.

- Lack of ‘common sense of mission and purpose’ (an apt phrase coined by HSUS’s John Hoyt when he was President of WSPA).

- Lack of professionalism and efficiency in many organizations.

- The lack of capacity, skills and expertise for dealing with animal welfare within the movement: This includes low numbers of animal welfare-trained veterinarians.

- Lack of strategic and operational impact.

- Lack of strategic advocacy.

- Lack of long-term, sustained campaigns.

- The detrimental effect of divisive attitudes in the movement – particularly as regards the welfare v rights debate (instead of accepting that all are working on same path – just on different steps along the way – and focusing efforts on the common ‘enemy’).

- The tendency towards competition, rather than genuine collaboration.

- Failure to develop feasible alternatives to current paradigms and orthodoxies.

- The breadth and range of issues covered by the movement and the lack of (agreed) focus and prioritization.

- Allocating the ‘lion’s share’ of resources to ‘service delivery’ work, as opposed to social change.

- The underdeveloped animal welfare movement (shortage of organizations, and human and financial resources), which has hampered the development of education and awareness – and advocacy.

- Lack of resources or skills necessary for successful coalition/alliance building.

- Lack of collaboration and support from other social justice movements.

- The lack of inclusion of animal welfare in all associated development projects (including: livestock and fisheries development, environment, education, wildlife etc.).

- Lack of funding (especially Trusts and Grants, favoring service delivery work).

- Lack of (development) funding for animal welfare initiatives.

- In ‘developing’ countries, the perception that animal welfare was/is a colonial ‘import’, or somehow a luxury for the privileged (whereas it is now based on science).

A recent in-depth study of 15 Southern African countries indicated that only 1 country in the region had a modern, comprehensive Animal Welfare Act, 7 had just basic anti-cruelty laws, and 5 had no Animal Welfare Act at all. There was evidence of ineffective animal welfare enforcement in all 15 countries. 13 countries had inadequate animal welfare structures within government. Levels of animal welfare awareness were low throughout the region, and two thirds of the countries in the region had poorly developed animal welfare movements (with 3 of these having no movement at all).

Interestingly, the main current driver of animal welfare in the Southern African region was found to be a ‘top down’ one, emanating from the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) and its national delegates. However, the lack of ‘bottom up’ pressure (from the animal welfare movement and individuals) in most countries in the region had led to a low level of political will which had frustrated real progress.

Identifying the ‘drivers’ of social change and adding power and weight to their work is considered a winning advocacy strategy. It is more effective to strengthen a positive force, than to try to counter a negative force (as this only brings a counter-reaction).

The current lack of modern animal welfare law is widely viewed as a major problem in many countries, particularly ‘developing’ countries. However, before this can be effectively developed it is important that necessary structures and systems – and expertise - are developed within government. These need to be able to deal effectively (ensuring participatory consultation) with policy analysis and formulation; the development of modern, comprehensive legislation; and the establishment of enforcement mechanisms that work.

However, in order for a policy and legislative framework to be effective in raising animal welfare standards, the level of education and awareness of animal welfare also needs to be raised. This is vital on two levels: Both for raising general public awareness – which is necessary to make animal welfare an issue of importance in society (which is part of the social change process) – and for training those responsible for the enforcement and implementation of animal welfare law (including officials and animal users).

The development of the animal welfare movement (civil society) would also assist the development of societal change in favor of animal welfare. The number of organizations in a country is an indicator of the general level of awareness and understanding of the issue. Thus, as education and awareness of an issue rise in a society (from the above interventions), this – in turn – leads to an increase in the number of organizations dealing with the subject. However, to be truly effective agents of change, animal welfare organization need to follow the general pattern of the civil society movement, and move from service delivery to strategic advocacy work.

This Southern African analysis considered the following to be needed in order to achieve sustainable social change for animal welfare:

Education and awareness

Needed to raise understanding, knowledge, support and implementation ability.

The animal welfare movement

Development needed to generate critical mass through advocacy, as well as practical animal welfare projects.

Policies, legislation, and enforcement

Which included animal welfare structures; Necessary for policy change.

The animal welfare movement is in dire need of a strong and forceful movement for social change. Advocacy is the engine for social change. Education is vital but longer-term, and service provision is not tackling problems at their root cause, but akin to applying ‘sticking plaster’ to a wound. The animal welfare policy environment is becoming increasingly ready for fundamental change, but this will not be achieved or sustained without a groundswell of pressure and support for reform. International organizations, governments and civil service departments are, by their very nature, cautious and favor maintenance of the status quo. The same could be said of consumers! All need strong reasons to act, which the movement has to provide – loud and strong!

'Service Delivery'

Service delivery work (working within the existing system - often known as ‘practical project work’) can detract from the movement’s time, capacity and political will to campaign forcefully for social change. Examples include legislative enforcement, stray control work and veterinary care. Because many in the movement are very empathetic, they cannot overlook immediate suffering and so get drawn into service delivery/practical work, rather than using their practical experiences as a basis for prioritising advocacy for lasting social change.

If the world’s animal shelters had spent as much time and effort on advocacy to change the plight of animals as they do picking up the sad end results that demonstrate so painfully the need for change, we could have seen a powerful (and probably successful) revolution! Of course, this is simplistic, as many animal shelters are better suited to service provision work, but the need for urgency and power is still relevant. Certainly every service provision animal welfare society should also advocate for change to the horrendous situation for animals which they face on a daily basis. If they do not do so, they are simply supporting an unjust system – taking responsibility and thus perpetuating the situation.

Also, major funders of animal welfare work, such as Trusts and Grants, have traditionally favored service provision activities. This is probably partly due to the more tangible, measurable and emotionally pleasing results gained from this type of work in the short-term. However, as these bodies – and individuals - become more familiar with the complex animal welfare environment, this perception is changing. More Trusts and Grants are beginning to realise that the service provision work they are funding, day-after-day, year-after-year, is failing to change the situation for animals in a real and lasting way. The only way to do this is through tackling the ‘root causes’ of these enduring problems. This may be longer-term, but it is sustainable.

Threats

Globalization Affecting the Movement

The main factors arising from globalization that impact upon the animal welfare movement are:

- The rise of powerful transnational corporations (TNCs) in animal-use industries.

- The emergence of powerful trading blocs, regional legislation/standards and international legislation/standards (either promoting or restraining/hampering action on animal welfare issues).

- The rapid spread of information and communication technologies.

- Increased travel opportunities and personal contacts amongst animal welfare groups internationally.

- The trend towards deregulation and ‘consumer choice’.

As markets globalize, the power of those who market (e.g. producers, supermarkets and – especially - fast-food outlets) increases in both strength and outreach. The animal use (and abuse) industries that are the opponents of the movement are becoming increasingly wealthy and political powerful. As leading Japanese management guru Kenichi Ohmae (1996) argues, capital, corporations, customers, communications, and currencies have replaced nation states as determinants in the global economy and have created regional economic zones that constitute growing markets for global corporations.

The animal welfare movement has to harness all its resources to counter this growing threat and to meet the challenges that the new international political scene is throwing forward. It needs to become a powerful international movement for social change: strategic, focused and professional – adept at leveraging its skills and capabilities internationally and supporting and assisting nascent and developing organizations across the world.

Progress with animal ethics in one country can also influence other countries. There is without doubt a moral influence from more advanced (in terms of animal welfare) countries. There is also their role in regional and international meetings.

Science

The way in which the authorities have come to rely on science alone is a real threat to the movement. This emphasis on ‘rationality’ is a result of a schizophrenic dualism, brought about by Greek philosophy and reinforced by the Enlightenment. However, it fails to recognize that facts are always interpreted through cultural screens (of which rationality is one). Intrinsic knowledge and wisdom is ignored until science ‘catches up’ with common knowledge. Unless the ‘precautionary principle’ is applied (to always give the animals the benefit of the doubt where science cannot provide the answers), then this leads to society consistently compromising the welfare of animals. It also leads to increased official support for biotechnological solutions, rather than natural methods and necessary protection.

However, as animal welfare science is developed, this is supporting the cause – as it ‘plays catch-up’ with our intrinsic knowledge and sense of justice.

Co-option

The danger of co-option is another present threat to the movement. This occurs not only with groups that are taken into the system through service delivery activities. It also occurs in other areas. In lobbying, for example, we increasingly see tokenism, instead of real engagement of a broad range of animal welfare interests. Consultation is simulated, but in reality input is discounted or ignored, particularly when weighed against commercial interests.

There are also examples of where animal welfare organizations are brought into compromise situations as regards the introduction of new legislation, enforcement or structural ‘advances’. The animal welfare movement appears even more willing than other movements to grasp at straws and settle for less than the optimum – possibly because after years in the ‘wilderness’ as a marginal interest it is simply too willing to be taken seriously at any level.

Previous Successes

There have been some excellent successes at European Union (EU) level, where there is now a body of animal welfare legislation that is in most cases stronger than national law. The use of networks and coalitions has doubtless played a fundamental role in these. These include:

- The Eurogroup for Animal Welfare, which has member organizations across the EU and lobbies at EU-level on the whole range of animal welfare issues.

- The European Coalition to End Animal Experiments (ECEAE), which is a pan-European coalition campaigning and lobbying to end animal experiments in Europe.

- The European Network for Farm Animal Protection (ENFAP), which was previously known as the European Coalition for Farm Animals (ECFA), which is an alliance of animal advocacy groups campaigning and lobbying together throughout Europe.

Progress was moved to an international level when the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) identified animal welfare as a priority in its strategic plan for 2001-20015, and started developing international standards covering animal welfare issues. Whilst these standards are lower than some European legislation, and some higher standard national animal welfare laws, they do represent enormous progress for the many countries with no (or very basic) animal welfare laws. Furthermore, the OIE consults the animal welfare movement, having WSPA as a ‘collaborating partner’ and member of its Animal Welfare Working Group (which drafts the standards), and WSPA widens this involvement through its coordinating body - the ‘International Coalition for Animal Welfare (ICFAW)’.

There have also been significant successes in some countries nationally – particularly within Europe, Australia and New Zealand. Far-reaching legislation is passed, and animal welfare activity is beginning to be accepted as a legitimate national interest (even being included in some constitutions).

Within Southern Africa, Tanzania has been seen to have made significant progress in animal welfare in recent laws. At least part of these advances must be attributable to the impact of advocacy from the World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA)’s African offices, following its relocation from Kenya to Tanzania.

Despite this, in some countries, such as India, the movement appears to be losing ground as other materialistic concerns take precedence amongst the youth (despite an ingrained culture in favor of animal concerns).

There have also been two significant developments which have the potential to strengthen the movement. These are the development of the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organizations (FIAPO) and the Pan African Animal Welfare Alliance (PAAWA). On the other hand, the dismantling by WSPA of its international member society network was a blow to many former member societies.

What is Needed for Success?

Firstly, the movement needs to understand its role as a social change agent. It needs to make its animal justice mission a real ‘raison d’être’, instead of just paying lip service to this. This should provide the real ‘fire in the belly’ that is needed to change the movement into a strong force for social change.

The rapidly changing commercial and political environment with which the animal welfare movement is faced, calls for some fundamental changes. It needs to become increasingly professional and strategic, using modern management methods appropriate to its complex environment.

To succeed in its mission, the movement needs to change its focus to tackling problems at source, rather than endlessly sweeping up the tragic end results. We need to put a stop to being taken advantage of in service delivery activities. If an organization wants, and needs, to do service delivery work, it should make absolutely sure that it is paid at the going economic rate for this. It should also ensure that this work does not lead to its ‘cooption’ into the existing flawed system, and that it always works for social change for animals.

The movement needs to draw a halt to being co-opted and neutralized. Every serious organization, of whatever ethical persuasion, should demand full and inclusive representation, not tokenism.

Competition is divisive and tears the movement to shreds. The industry is far stronger in terms of people and resources. Their political clout can be measured in economic building blocks, whereas the movement’s building blocks are far more ethereal and fragile – ethics, morality and the power of good. They can only counter the economic threat if they are placed in a coherent stack, rather than small individual piles, that others are constantly trying to kick into the dust. We need the glue of coherence and unity. We need effective collaboration and alliances across the movement. Only then will consumers and voters begin to adopt the coherent message, instead of giving up in the face of all the noise and confusion.

Advocacy is the engine of the movement for social change. The movement’s campaigning methods need to be updated and dynamic if we are to succeed. In most countries across the world, the days are gone when a small demonstration with placards and a campaign mascot could sway governments. The forces pitted against us are too strong and powerful to be combated with such simplicity. We need to generate a groundswell of pressure and support for reform. This will take new ammunition and new targets. Campaign targets have been changing with the move from regulatory to market-orientated environments – from government and voters, towards business targets and consumers. An in depth understanding of the political and external environment is vital. Campaigns need to be hard-hitting, with focus and impact, but also well-researched. They must be combined with a strong, professional lobby, avoiding the usual NGO pitfalls. Every country should be pressed to recognize animals as sentient beings, not just property, and have fully enforced modern animal welfare laws (instead of the existing situation where less than one third of countries have laws at the time of writing).

Humane education is vital to the development of a humane ethic in future generations, and the movement.

The animal welfare movement is quite clearly one of the great movements for social change, but it has yet to reach its real potential and impact. We need to root out exploitation of animals wherever it has become ingrained into our society and institutions (Midgely), and to expose and shame. We must never let the unacceptable become the status quo. We must change hearts and minds before it is too late.

Social Change Movements

Introduction to Social Movements

Social Movement Organizations

Types of Social Movement

Dynamic of Social Movements

Stages of Social Movement

Inspiring Social Change Movements

Introduction to Social Movements

There are numerous definitions of social movements. However, the core of the concept is included in Wilson’s (1971: 8) definition: ‘A social movement is a conscious, collective, organized attempt to bring about or resist large-scale change in the social order by non-institutionalized means.’

Social movements develop because there is a perceived gap between the current ethics and aspirations of people and the present reality. As Wilson said: ‘Animated by the injustices, sufferings, and anxieties they see around them, men and women in social movements reach beyond the customary resources of the social order to launch their own crusade against the evils of society. In so doing they reach beyond themselves and become new men and women.’

Because social movements are the consequences of new elements of civil society, which are not incorporated into the social order, they are always unconventional. Civil society is normally in a state of change, but social structures tend towards stability. That is why social movements almost always exist. If the discrepancy between civil society and social order is large, then social movements are strong and numerous. If the discrepancy is small, then social movements are weak and more conventional.

This ‘disenfranchisement’ leads to mobilization – first organizational, where resources are harnessed in support of the cause. Resources include: people, time, skills/expertise and funds. Then mass mobilization, where society is recruited behind the cause.

There is inevitable resistance to social change. Many do not want their vested interests or status quo threatened. There is also simple inertia.

Tactics of change: non-violence includes negotiation, direct action, events/media stunts, demonstrations, propaganda, strikes, boycotts, non-co-operation, civil disobedience, parallel structures. Violent breakaway groups undercut the movement’s legitimacy.

Actions undertaken by civil society to effect change are generally informed by strategic thought. In thinking strategically, social change activists try to identify the nature and causes of social problems and then choose specific targets that are deemed the most likely people or organizations to resolve those problems. One of the keys to a successful strategic approach is in maintaining effective communication with, and among, members of the public.

It is readily acknowledged by leading social theorists (Arendt, 1958; Habermas, 1989) that just and effective democracies require a strong and functional public sphere. The public sphere operates best where citizens, as individuals or in groups, are informed about the social, political and corporate affairs that affect their interests, and enter into public discussion about the plans, policies and activities of those in power whose decisions affect their area of concern. This on-going discussion provides the feedback and direction needed for healthy governance.

Social Movement Organizations

Organizing New Social Change Activities: The surplus energy accumulated by the society and given expression through the initiative of pioneers and their followers does not gain momentum until it becomes accepted and organized by society. The process of organization may take many different forms. It may occur by the enactment of new laws or regulations that support the activity or it may be in the form of a new system or accepted set of practices. Each development advance of the society leads to the emergence of a host of new organizations designed to support it and puts pressure on existing organizations to elevate their functioning to meet the higher demands of the new phase.

Integrating the Organization with Society The organization is the mechanism by which the surplus energy in society is harnessed, mobilized, directed and channeled to produce greater results. The organization derives energy from being integrated with the society in which it functions. The energy of society comes from its needs and aspirations. This energy pervades the social organization established to meet these needs. The more finely the organization is attuned to fulfil underlying social aspirations, the greater the energy flowing through it.

The will of society changes over time as old attitudes and goals are replaced with new ones. Organizations that adapt to these changes continue to thrive. Those that remain fixed in the past decline, become ineffective, and are eventually discarded or fade away

Types of Social Movements

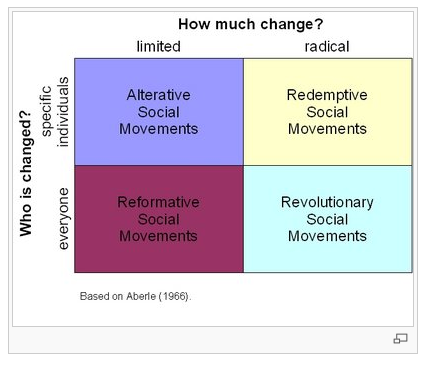

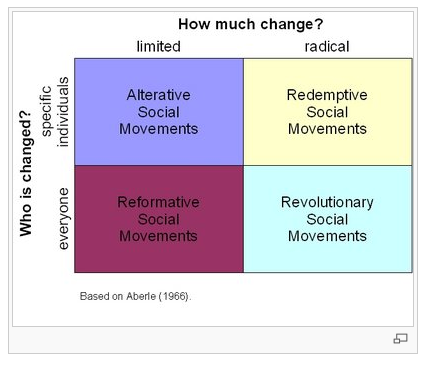

David Aberle (1966) described four types of social movement including: alterative, redemptive, reformative, and revolutionary social movements, based upon two characteristics: (1) who is the movement attempting to change and (2) how much change is being advocated.

A. Alternative Social Movements are looking at a selective part of the population, and the amount of change is limited due to this. Planned Parenthood is an example of this, because it is directed toward people of childbearing age to teach about the consequences of sex.

B. Redemptive social movements also look at a selective part of the population, but they seek a radical change. Some religious sects fit here, especially the ones that recruit members to be ‘reborn’.

C. Reformative social movements are looking at everyone, but they seek a limited change. The environmental movement fits here, because they try to address everyone to help the environment in their lives (like recycling).

D. Revolutionary social movements want to change all of society. The Communist party is an example of wanting to radically change social institutions.

This is shown diagrammatically below.

Reform Movements - movements dedicated to changing some norms, usually legal ones. Examples of such a movement would include a green movement advocating a set of ecological laws, or an animal welfare organization advocating controls on animal experimentation. Some reform movements may advocate a change in custom and moral norms, for example, condemnation of pornography.

Radical Movements - movements dedicated to changing some value systems. It directs to the creation of new social order and the destruction of existing social order. Those are usually much larger in scope then the reform movements, Examples would include the American Civil Rights Movement which demanded full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans, regardless of race. An animal rights organization demanding an end to all animal use would fall into this category.

Methods of Work:

Peaceful movements - opposed to using violent means. The American Civil Rights movement, Polish Solidarity movement, or Mahatma Gandhi civil disobedience movements would fall into this category. Animal welfare organizations fit into this category.

Violent movements - various armed resistance movements up to and including terrorist organizations. Examples would include the Palestinian Hezbollah, Basque Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) or Ireland’s Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) movements. Some animal liberation groups fit into this category (but not all, as some following a liberation philosophy use peaceful methods).

Old and New

Old movements - most of the 19th century movements that recruited their followers from a specific social class (only workers, only peasants, only Aristocrats, only Protestants etc.). They were usually centered on some materialistic goals like improving the living standard of the given social class.

New movements - movements which became dominant from the second half of the 20th century - like the civil rights movement, environmental movement, gay rights movement, peace movement, anti-nuclear movement, anti-globalization movement, etc. Sometimes they are known as postmodernism movements. They are usually centered on a non-materialistic goal.

Dynamic of Social Movements

Social movements are more likely to evolve in the time and place which is friendly to the social movements: hence their evident symbiosis with the 19th century proliferation of ideas like individual rights, freedom of speech and civil disobedience. There must also be polarizing differences between groups of people: in case of 'old movements', they were the poverty and wealth gaps. In case of the 'new movements', they are more likely to be the differences in customs, ethics, and values.

Finally, the birth of a social movement needs what sociologist Neil Smelser calls an initiating event: a particular, individual event that will begin a chain reaction of events in the given society leading to the creation of a social movement. For example, American Civil Rights movement grew on the reaction to black women, Rosa Parks, riding in the whites-only section of the bus. The Incident of Rosa Parks who was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to make room for white people sparked the American Civil Rights Movement. The Polish Solidarity movement, which eventually toppled the communist regimes of the Eastern Europe, developed after trade union activist Anna Walentynowicz was fired from work. Such an event is also described as a volcanic model - a social movement is often created after a large number of people realize that there are others sharing the same value and desire for a particular social change.

Thus, one of the main difficulties facing the emerging social movement is spreading the very knowledge that it exists. Second, is overcoming the free rider problem - convincing people to join it, instead of following the mentality 'why should I trouble myself when others can do it and I can just reap benefits after their hard work'.

Social movements can organize or mobilize in order to spread their issue. Mobilizing refers to the process by which inspirational leaders or other persuaders can get large numbers of people to join a movement or engage in a particular movement action, while organizing refers to a more sustained process whereby people come to deeply understand a movement's goals and empower themselves to continued action on behalf of those goals.

Stages of Social Movements

After the social movement is created, there are two likely phases of recruiting. The first phase will gather the people deeply interested in the primary goal and ideal of the movement. The second phase, which will usually come after the given movement had some successes and its fame increased, will gather people whose primary interest lie in joining the movement for 'being in it' - because it is trendy, or would look good on a résumé. People who joined in this second phase will likely be the first to leave when the movement suffers any setbacks and failures.

Eventually, the social movement will move towards a crisis. If it has achieved its intended goal, then it's called a victory crisis, as most members leave the movement assuming there is no longer any need for its continued existence. This will likely be opposed by a minority of members, for whom the existence of the very movement have become the primary goal itself, and likely the source of their income. Few social movements have survived a victory crisis, often merging with other similar movements or transforming into a tiny, caricature form of their early selves. Other type of crisis is a failure crisis, which can be seen in increasing demoralization and disenchantment of members, when they loose faith in the possibility that the primary goal of the movement can be ever achieved. Failure crisis can be encouraged by outside elements, like opposition from government or other movements. However, many movements had survived a failure crisis, being revived by some hardcore activists even after several decades.

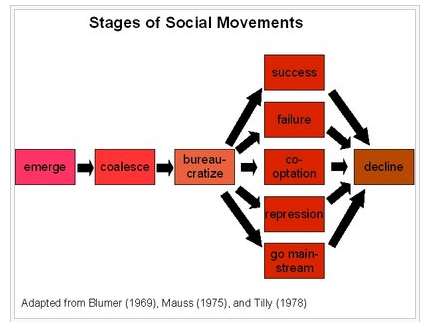

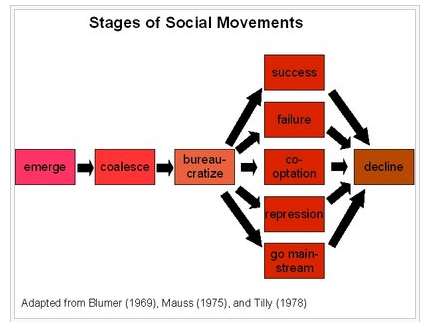

Blumer (1969), Mauss (1975), and Tilly (1978) have described different stages social movements often pass through. Movements emerge for a variety of reasons (see the theories below), coalesce, and generally bureaucratize. At that point, they can take a number of paths, including: finding some form of movement success, failure, co-optation of leaders, repression by larger groups (e.g., government), or even the establishment of the movement within the mainstream.

Social movements have a lifecycle of their own, and move through various stages that include:

Incipiency

The birth of the movement

Coalescence

The movement becoming a co-operative force

Institutionalization

Develops into an institution

-or-

Fragmentation

Falls apart

Inspiring Social Change Movements

There are a number of different social movements, which it is useful to study to gain inspiration, ideas and methodologies. This can also help you to understand social movement theories and how these work in practice.

We have selected some of the most inspiring social movements; and examined these - and their ‘ways of working’ - briefly below for the purposes of this course. Some key principles from these movements are also included below.

Gandhi and Non-Violence

Gandhi’s greatest achievement was to develop the philosophy of non-violent action, and spread this concept throughout the world. Born on October 2, 1869, Mohandas Gandhi struggled to find freedom for his Indian countrymen and to spread his belief in non-violent resistance.

Part of the inspiration Gandhi’s policy of non-violence came from the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, whose influence on Gandhi was profound. Gandhi also acknowledged his debt to the Bhagavad Gita, the teachings of Christ and to the 19th-century American writer Henry David Thoreau, especially to Thoreau's famous essay ‘Civil Disobedience’.

It was in South Africa that Gandhi first experienced racial discrimination. There he began his fight to end prejudice and achieve equality for people of all races. Using marches, letters, articles, community meetings and boycotts, he protested. These protests often led to his arrest.

After 21 years in South Africa, Gandhi returned to India to fight for Indian independence from Great Britain. In addition to the methods he used in South Africa, Gandhi would add fasting and prayer to his system of non-violence.

The six strategic steps on non-violent direct action (Principles of Nonviolent Direct Action) which Gandhi developed were as follows:

- Investigate: Get the facts. The complexity of society today requires patient investigation to accurately determine responsibility for a particular injustice.

- Negotiate: Meet with opponents and put the case to them. A solution may be worked out. If no solution is possible, let your opponents know that you intend to stand firm to establish justice, but that you are always ready to negotiate further.

- Educate: Keep campaign participants and supporters well informed about the issues, and spread the word to the public.

- Demonstrate: Picketing, holding vigils, mass rallies, and leafleting are the next steps.

- Resist: Non-violent resistance is the final step, to be added to the first four as a last resort. This may mean a boycott, a fast, a strike, tax resistance, a non-violent blockade or other forms of civil disobedience. Planning must be carefully done, and non-violence training is essential. When properly carried out, actions of resistance build a position of moral clarity, which will strengthen your own courage and create widespread respect for your campaign.

- Be patient: Meaningful change cannot be accomplished overnight. To deepen ones analysis of injustice and oppression means to become aware of how deeply entrenched are the structures, which produce them. These structures can be eliminated, but this requires a long-term commitment and strategy.

Social Change Now gives an example of Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence in action. This shows the strategic and proactive (not to mention brave!) nature of such actions: - ‘On April 6, 1930, after having marched 241 miles on foot from his village to the sea, Mohandas K. Gandhi arrived at the coastal village of Dandi, India, and gathered salt. It was a simple act, but one which was illegal under British colonial rule of India. Gandhi was openly defying the British Salt Law. Within a month, people all over India were making salt illegally.’ Many were jailed, but the ‘soul force’ of Gandhi’s campaign was too strong to be cowed and curbed.

The Gandhian Institute of Bombay stresses that Gandhi rejected the term and concept of ‘passive resistance’, because of its insufficiency and its being interpreted as a weapon of the weak. They state that non-violence is militant in character.

Gandhi disliked both the terms ‘passive resistance’ and ‘civil disobedience’ to describe his approach, and coined another term, ‘Satyagraha’ (Sanskrit, ‘truth and firmness’). Satyagraha has also been called ‘soul force’.

Gandhian principles played a part in inspiring similar movements throughout the world, removing dictators over the last 15 years in countries as far apart as the Philippines and Poland, while providing the inspiration for the American civil rights leader, Martin Luther King. In 1959, Dr. and Mrs. King spend a month in India studying Gandhi’s techniques of non-violence as guests of Prime Minister Jawaharal Nehru.

The US Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights Movement in the United States was a struggle by black Americans to gain full citizenship rights and achieve racial equality. Individuals and organizations challenged discrimination with a variety of activities, including protest marches, boycotts, and refusal to abide by segregation laws. Many believe that the movement began with the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955 and ended with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, though some argue that it has not ended yet.

The Civil Rights Movement in the United States had two clear strands:

- Reform: The Southern Christian Leadership Council. Luther King's non-violent approach.

- Revolutionary: The Black Panthers, Malcolm X

Malcolm X rejected non-violence as a principle, but he sought co-operation with Martin Luther King and other civil rights activists who favoured aggressive non-violent protests.

Martin Luther-King studied Gandhi’s principles and methods. However, as Robert Frick (Ph.D.) noted his situation was slightly different from Gandhi's, so he needed slightly different principles.

The major principles of King’s non-violence movement were:

- Non-violence is a way of life for courageous people.

- Non-violence seeks to win friendship and understanding

- Non-violence seeks to defeat injustices, not people

- Non-violence holds that suffering for a cause can educate and transform

- Non-violence chooses love instead of hate

- Non-violence holds that the universe is on the side of justice and that right will prevail

Martin Luther King, and his policy of non-violent protest, was the dominant force in the civil rights movement during its decade of greatest achievement, from 1957 to 1968. His lectures and remarks stirred the concern and sparked the conscience of a generation. The movements and marches he led brought significant changes in American life. Strategic direct action became the movement’s salient strategic weapon. The tactics employed included:

- Sit-ins

- Freedom riders (on buses)

- Demonstrations and Marches

There is further information on these below.

King summoned together a number of black leaders in 1957 and laid the groundwork for the organization now known as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). King was elected its president, and he soon began helping other communities organize their own protests against discrimination.

Dr. King’s concept of 'somebodiness' gave black and poor people a new sense of worth and dignity. His philosophy of non-violent direct action, and his strategies for rational and non-destructive social change, electrified the conscience of this nation and re-ordered its priorities. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, for example, went to Congress as a result of the Selma to Montgomery march. His wisdom, his words, his actions, his commitment, and his dreams for a new cast of life fired the movement. His 1963 ‘I Have a Dream’ speech dealing with peace and racial equality is one of the most powerful speeches in American history.

The tactics employed by King’s movement included:

Sit-ins

In 1960, four black students asked to be served at Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, reserved for white customers only. When refused they staged a sit-in protest. By 1961, 70,000 had taken part in similar sit-ins. These protests gained publicity for the plight of blacks in the South.

Freedom Riders

These were groups of black and white protesters who rode segregated buses across the Southern States. Sometimes, they were ambushed and attacked by white youths. When they reached their destination – usually a heavily segregated town, they would organize sit-ins. Freedom riders got great publicity for the Civil Rights cause.

Demonstrations and Marches

Peaceful demonstrations and marches were very powerful Civil Rights tactics. When demonstrators were attacked by white police forces e.g. Birmingham, Alabama, April 1963, (dogs, fire hoses and cattle prods used) public opinion came down on the Civil Rights protestors, rather than bigoted police chiefs.

King was recipient of the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, which increased his credibility enormously.

After 1965 the focus of the civil rights movement began to change. Martin Luther King, Jr., focused on poverty and racial inequality in the North. Younger activists criticized his interracial strategy and appeals to moral idealism. In 1968, King was assassinated by a gunman in Memphis, Tennessee.

For many, the civil rights movement ended with the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. Some argue that the movement is not yet over because the goal of full equality has not been achieved. Racial problems still exist, and urban poverty among black people is a social reality.

The Environmental Movement

The environmental movement has its roots dating back into the 1890s. When it began life, it was mainly a movement composed of people from the better off sectors of society, who were concerned about issues of preservation or management of the wilderness, and whose critique of society did not generally go beyond these concerns.. It was a conservative movement.

The modern environmental movement did not develop until the 1960s when it became more of a social change movement, with radical strands. This was an era of real social change (free speech, civil rights, women’s rights, anti-war etc.), with increased concern over issues such as toxic chemicals, polluted air and water etc..

The movement was fuelled by Rachel Carson’s book ‘Silent Spring’ in 1963 (which exposed the effects of DDT - a ‘pest’ spray that killed insects, entered the food chain and caused cancer and genetic damage – and led to it being banned from the market) and by crises such as the toxic smogs in the UK and USA from the 1940s to the 1960s. It broadened its focus to become concerned not only with protecting the wilderness, but also with the impact of environmental degradation on people's daily lives.

However, the ‘Environmental History Timeline’ states that although ‘Silent Spring’ fuelled the movement, it is clear that long before Silent Spring was written (or Greenpeace activists defied whalers’ harpoons!) many thousands of ‘green crusaders’ tried to stop pollution, promote public health and preserve wilderness.

In the sixties and seventies a radical environmental movement began to emerge made up of groups concerned with the degradation of the environment not as a wilderness issue, but as a part of daily life. Recycling was promoted, and wider issues such as the dangers of chemicals in the food chain, polluted air and water etc. were promoted to persuade people that protection of the environment was an important issue. Most of the people involved in these groups were young people, influenced by the antiwar movement and by the counterculture.

At roughly the same time, some progressive labor activists were beginning to raise issues having to do with occupational safety and health, with the presence of toxic chemicals and other environmental hazards in the workplace. Both labor environmentalism and radical environmentalism (or ecology, as it was usually called) were concerned not only with protecting the wilderness, but also with the impact of environmental degradation on people's daily lives.

In the seventies both radical and mainstream environmentalism grew, but both sectors of environmentalism remained overwhelmingly white and, except for efforts by labor activists around occupational safety and health, overwhelmingly composed of middle and upper-middle class people, especially students and professionals.

In the late seventies and early eighties a new grassroots environmental movement began to emerge involving constituencies previously distant from environmentalism: lower middle class and working class whites, colored people and rural communities. The movement then began to ‘take off’, with rapid growth of the number of environmental organizations and issues covered, and a wider variety of approaches (from practical/service delivery to radical advocacy, with a broad base of mainstream/populist support).

The range of environmental issues that organizations campaign about is now vast (covering issues such as water, air, forests, wetlands, animals and habitats, anti-war and anti-nuclear, and wastes).

The environmental movement has grown into a powerful force, which gathers more political and popular support with the emergence of each new environmental crisis. Also, unlike most social change movements, it benefits from extremely concrete benchmarks (things like tons of CO2 emissions prevented; acres of rainforest and coral reef preserved; species saved from extinction etc.). However, in terms of the ultimate conservation objective of building a civilization that can thrive on this planet without destroying it, then the movement could be said to be failing.

Watch these YouTube videos!

A powerful video depicting social change through resistance. If they did it, so can you!

Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech