42. Advocacy Evaluation Case Study

Category:

Optional

Description and Purpose:

This tool is an example of an advocacy evaluation case study.

Method:

Analyze and write up an advocacy case study, using the following questions as a guide to structure.

The case study should take three to five minutes to explain.

- What was the problem?

- Who decided to advocate on the problem (i.e. brief details of the NGOs/AW organizations involved)?

- What was the advocacy objective?

- Who did you advocate to?

- What methods did you use?

- What difficulties did you face?

- How did you overcome any difficulties?

- What were the results of your advocacy?

- What factors (or activities) contributed to these results?

- 1If appropriate: where did you obtain the evidence or information that was used?

- 1What sources of assistance/support did you find most helpful?

- What did you learn from doing this advocacy?

- Why do you think this is an important example?

- What do you think your organization could learn from this example?

Use photos, drawings or other ‘visuals’ to provide a human/animal angle to your information. Are the people and organizations featured in your case study aware of how it might be used, and what the consequences might be?

Consider including the following:

- Content & Process

- Description of change – initial situation; what has changed; how it happened

- Explanation for choice – who was involved; why this change is meaningful/relevant

- Lessons/recommendations – what this change tells us

- Selected by participants as part of review process

- Reasons for choice and lessons/recommendations for follow-up discussed as part of selection process

40. Negotiation Technique Tips

Category:

Recommended

Description and Purpose:

Tips on negotiation techniques.

Method:

Consider the following tips on negotiation techniques, and try to incorporate any that are suitable for your situation.

Negotiation Techniques

Negotiation is a process, not an event. There are predictable steps: preparation, creating the right climate, identifying interests, and selecting outcomes, that you will go through in any negotiation. The following are some tips to help with this process.

Know Yourself

Assess your strengths and weaknesses. Use your strengths and avoid or play down your weaknesses.

Do Your Research

Know who you’re negotiating with. What’s his or her reputation as a negotiator? Know their likes and dislikes, and past record.

Style

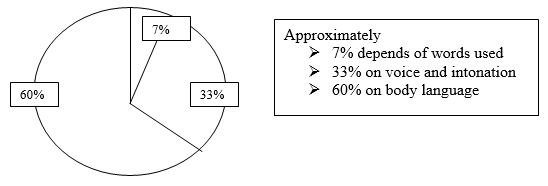

Develop a sympathetic style of negotiation technique, and adapt this to suit the other party. The negotiation should leave a positive atmosphere, and not be antagonistic. Use body language and props effectively, and make good use of timing.

Practice Double and Triple Think

It’s not enough to know what you want out of negotiation. You also need to anticipate what the other party wants (double think). The smart negotiator also tries to anticipate what the other party thinks you want (triple think).

Really good negotiators are able to read the other person/people. They can take the role of an Objective Observer, retaining a calm, inner state of mind.

Build Rapport

Build a relationship over time. Be like them, and make them like you!

Build Trust

Without trust, there won’t be communication. Always be honest and trustworthy. Respect confidences, and deliver commitments.

Develop External Listening

Your inner dialogue (and worries) can stop you listening to others effectively. You should turn off this inner dialogue and concentrate on listening externally. Then you won’t miss important non-verbal messages, facial expressions of voice inflections etc. Also, use open questions, and check out anything you don’t understand.

Move Beyond Positions

In a negotiation, begin by stating your position. Later, when the trust has deepened, you and the other party can risk more honesty and identify your true interests. As a negotiator, you should ask questions that will uncover the needs or interests of the other party.

Own Your Power

Don’t assume that because the other party has one type of power, e.g. position power, that he or she is all-powerful. That is giving away your power! Assess the other party’s power source, and also your own. And use this! Your power will include internal power (for example, self-esteem, self-confidence etc.), as well as external power.

Know Your BATNA

BATNA stands for Best Alternative to A Negotiated Agreement. Before you begin a negotiation, know what your options are. What trade-offs are there? Can you walk away from the deal? What other choices do you have? What are the pros and cons of each choice? Effective negotiators are able to let go of their positions, giving up one want and choosing another.

Five Basic Principles

- Be hard on the problem and soft on the person

- Focus on needs, not positions

- Emphasize common ground

- Be inventive about options

- Make clear agreements

The following may also be helpful:

|

12 Principles to Win People to Your Way of Thinking

- The only way to get the best out of an argument is to avoid it.

- Show respect for the other person’s opinions. Never say: ‘you are wrong’.

- If you are wrong, admit it quickly and emphatically.

- Begin in a friendly way.

- Get the other person saying ‘yes’ immediately.

- Let the other person do a great deal of talking.

- Let the other person feel that the idea is his or hers.

- Try honestly to see things from the other person’s point of view.

- Show sympathy with the other person’s ideas and desires.

- Appeal to the nobler motives.

- Dramatize your ideas.

- Throw down a challenge.

Source: Carnegie (1953)

|