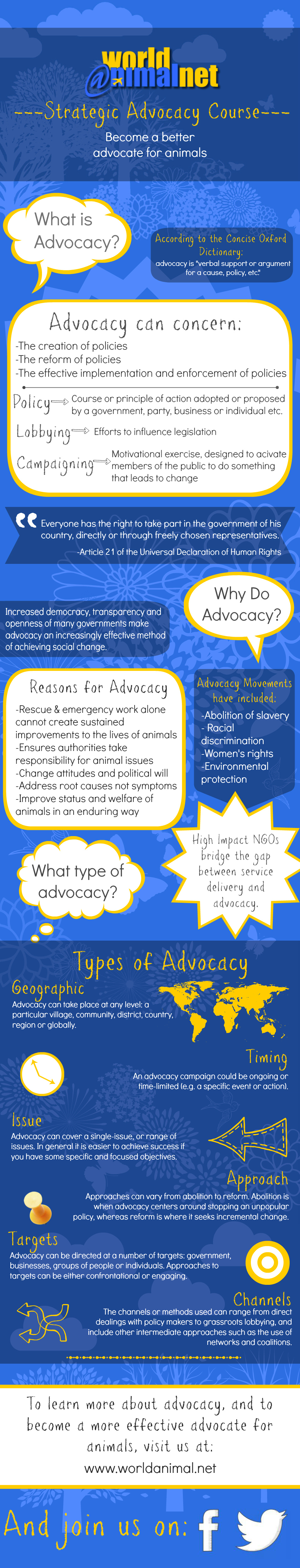

Infographic: What is Advocacy?

Advocacy campaigns by those with less power attempting to influence those with power over them have existed for as long as the power inequalities themselves. They have been documented in many countries for centuries (for example: nationalist and anti-taxation movements in colonized countries; and land’ reform and protectionist movements in post-colonial countries). Advocacy campaigns led by the privileged advocating on behalf of others have included the movements against slavery, racial discrimination, and for women’s rights.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, leading development NGOs became aware that development and emergency work alone was unlikely to produce sustained improvements in the lives of the poor. This lead them to re-examine their strategies, and they started to become increasingly focused on advocacy work. Advocacy work enables them to draw on their program experience to show the impact of existing policies on the poor and marginalized, and to suggest improvements.

The increased democracy, transparency and openness of many governments make advocacy an increasingly effective method of achieving social change. The general trend is for civil society to focus increasingly on advocacy, making government take responsibility for social issues (as opposed to taking over service delivery to ‘fill the gaps’). There are an increasing number and range of advocacy initiatives, with a greater degree of professionalism – and these are now often supported by private foundations (like the Ford Foundation), bilateral donor countries and international donors (such as the World Bank, which has established a ‘Community Empowerment and Social Inclusion Learning Program’ (CESI)).

The animal welfare movement is also developing its advocacy work. There have been animal rights/welfare demonstrations, and animal welfare lobbying, for many decades. Federations, coalitions and alliances have also been formed, including the World Society for the Protection of Animals and one of its predecessors – the World Federation for the Protection of Animals (WFPA), which was founded way back in 1953. However, the movement has been relatively slow in developing effective strategic advocacy, with integrated research and investigations, networking, campaigning and lobbying.

The first truly international animal welfare campaign was launched by WSPA in 1988. This was its successful ‘No Fur’ campaign, which was led by Wim de Kok (now WAN President). It was adopted by over 50 WSPA member organizations and took the arguments against the wearing of fur to all corners of the globe. One of the reasons for the successful roll-out of the campaign was its appealing campaign materials, which used the image of a baby fox with the message: “Does your mother have a fur coat? His mother lost hers…” The campaign keeps on running. It was recently used in China - in a strategic campaign launched by ACT Asia in the autumn of 2011.

These days many of the leading animal welfare organizations carry out strategic advocacy. But many organizations in ‘developing’ countries and local groups continue to concentrate on compassionate, practical animal welfare work – i.e. service delivery, as opposed to advocacy.

There are, however, strong reasons for developing advocacy work. These include the following:

We also recognize that advocacy can benefit other aspects of our work including: visibility, recruitment, fundraising etc. It can help animal welfare organisations to be recognized as a serious player in civil society circles and provide greater public exposure.

Research carried out at the USA’s ‘Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship’ confirms that although high impact NGOs may start out through designing great programs on the ground, they eventually realize that they cannot achieve large-scale social change through service delivery alone. So they add policy advocacy to change legislation and acquire government resources.

Other NGOs start out by doing advocacy and later add grassroots programs to ‘supercharge’ their strategy. But, ultimately, all high-impact organizations bridge the divide between service delivery and advocacy. They become good at both. And the more they serve and advocate, the more they achieve impact. The NGO’s grassroots work helps to inform its policy advocacy, making legislation more relevant, and advocacy helps the NGO to achieve its policy and program objectives.

There are many different types of advocacy work. These should be carefully considered to ensure that the approach adopted is appropriate to your organisation’s ‘ways of working’, the national strategy and country situation, and the aims of the advocacy campaign. There various ways in which to categorize types of advocacy including:

Geographical

Advocacy can take place at any level – in a particular village, community, district, country, region or globally.

Timing

An advocacy campaign could be ongoing or time-limited (e.g. a specific event or action).

Issue

Advocacy can cover a single-issue, or range of issues. In general it is easier to achieve success if you have some specific and focused objectives.

Approach to Issue

Approaches can vary from abolition to reform. Abolition is when advocacy centers around stopping an unpopular policy, whereas reform is where it seeks incremental change. Abolition is likely to be more confrontational (and publicly critical of the existing ideology), whereas reform is usually viewed as more co-operative and/or practical.

Targets

Advocacy can be directed at a number of targets: government, businesses, groups of people or individuals.

Approach to advocacy targets

This can vary from conflict to engagement. Conflict or ‘adversarial advocacy’ is often associated with ardent abolition or protest movements who document the failures of government or policy makers, criticize them ('mobilizing shame'), and thereby effect change. ‘Programmatic engagement’ is more commonly undertaken by organisations that work with government to deliver services. It involves constructive discussion of policies to effect internal reform and capacity building within existing systems.

Channels or methods used

The channels or methods used can range from direct advocacy (direct dealings with policy makers) to grassroots lobbying (mobilizing the public to make representations to policy makers), and include other intermediate approaches such as the use of networks and coalitions.

Advocacy that is aimed at changing the policies and practices of institutions has been categorized under the following four approaches:

A collaborative approach can be very effective if the policy-maker is open to change.

The rational approach can work if policies are made on a rational basis (rather than from political or self-interest motives). However, even when this is not the case, the rational approach is often an essential foundation for other approaches.

The political approach recognizes the different forces acting on policy decisions, and tries to build its own agenda into these forces.

The judicial approach can work when the judicial system is fair and independent, and has the authority and power to enforce its judgments. However, it is confrontational and can be slow, expensive and demand specialist skills.

Advocacy is both a science and an art. From a scientific perspective, there is no universal formula for effective advocacy. However, experience shows that advocacy is most effective when it is well-researched and strategically planned. Successful advocacy networks frame their issue, research the policy environment and audience, set an advocacy aim and measurable objectives, identify sources of support and opposition, develop compelling messages, mobilize necessary funds, and collect data and monitor their plan of action at each step along the way.

Advocacy is also an art. Successful advocates develop a ‘sixth sense’ about opportunities, timing, and people – and harness their knowledge in support of the campaign. This comes with experience, and from paying attention to these aspects.

The 'art' of successful advocacy involves:

The recipe for successful advocacy will differ from country-to-country – depending on the culture and political environment. In some countries the development of personal contacts is vital. However, this does not negate the need for thorough research and an effective strategy.